GPS-Derived Fault Coupling of the Longmenshan Fault Associated with the 2008 Mw Wenchuan 7.9 Earthquake and Its Tectonic Implications

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. GPS Data and Modeling Strategies

2.1. GPS Data and Its Processing

2.2. Modeling Strategies

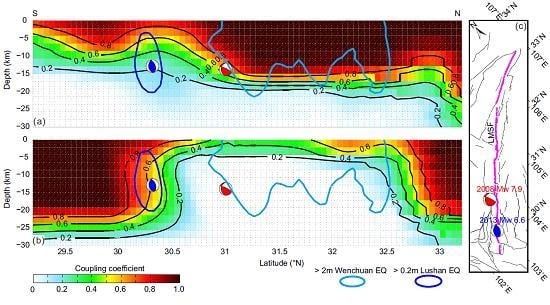

4.2. Nucleation and Occurrence of the 2013 Mw 6.6 Lushan Earthquake

4.3. Was the 2013 Mw 6.6 Lushan Earthquake an Aftershock of the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan Earthquake?

4.4. Seismic Hazard along the Southern LMSF

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burchfiel, B.; Royden, L.; vander Hilst, R.; Hager, B.; Chen, Z.; King, R.; Li, C.; Lü, J.; Yao, H.; Kirby, E. A geological and geophysical context for the Wenchuan earthquake of 12 May 2008, Sichuan, People’s Republic of China. GSA Today 2008, 18, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Wen, X.; Yu, G.; Chen, G.; Klinger, Y.; Hubbard, J.; Shaw, J. Coseismic reverse- and oblique-slip surface faulting generated by the 2008 Mw 7.9 Wenchuan earthquake, China. Geology 2009, 37, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royden, L.; Burchfiel, B.; King, R.; Wang, E.; Chen, L.; Shen, F.; Liu, P. Surface deformation and lower crustal flow in eastern Tibet. Science 1997, 276, 788–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapponnier, P.; Xu, Z.; Roger, F.; Meyer, B.; Arnaud, N.; Wittlinger, G.; Yang, J. Oblique stepwise rise and growth of the Tibet Plateau. Science 2001, 294, 1671–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu-Zeng, J.; Zhang, Z.; Wen, L.; Tapponnier, P.; Sun, J.; ** tools: Improved version released. Eos Trans. AGU 2013, 94, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Shan, X.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Liang, H.; Qu, C.; Song, X. GPS-Derived Fault Coupling of the Longmenshan Fault Associated with the 2008 Mw Wenchuan 7.9 Earthquake and Its Tectonic Implications. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10050753

Li Y, Zhang G, Shan X, Liu Y, Wu Y, Liang H, Qu C, Song X. GPS-Derived Fault Coupling of the Longmenshan Fault Associated with the 2008 Mw Wenchuan 7.9 Earthquake and Its Tectonic Implications. Remote Sensing. 2018; 10(5):753. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10050753

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yanchuan, Guohong Zhang, **njian Shan, Yunhua Liu, Yanqiang Wu, Hongbao Liang, Chunyan Qu, and **aogang Song. 2018. "GPS-Derived Fault Coupling of the Longmenshan Fault Associated with the 2008 Mw Wenchuan 7.9 Earthquake and Its Tectonic Implications" Remote Sensing 10, no. 5: 753. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10050753