1. Introduction

The realization of the goal of carbon neutralization is inseparable from the large-scale application of clean energy, which is mostly converted into electricity for use, and it is urgent to develop advanced energy storage devices to efficiently store and utilize clean energy [

1,

2,

3]. Lithium-ion batteries are efficient energy storage devices that have been widely used in large-scale energy industry, transportation, and consumer electronic devices [

4]. However, due to the limited progress in the research of cathode materials, the electrochemical performance of lithium-ion batteries is enhanced slowly [

5]. Currently, the main commercialized cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries are olivine-type phosphate systems, spinel-type oxide systems, and layered oxide systems; examples include LiFePO

4 [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11], LiMn

2O

4 [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19], LiCoO

2 [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], LiMnO

2 [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36], and LiNi

0.8Co

0.1Mn

0.1O

2 [

37,

38]. These cathode materials possess unique advantages, but they also have a common disadvantage; that is, relying on cationic redox reactions to contribute to a specific capacity means that the overall specific capacity is not high enough. Thus, there is a pressing need to develop high-specific capacity cathode materials for advanced lithium-ion batteries [

39].

Li-rich Mn-based cathode materials (LRM, xLi

2MnO

3·(1−x)LiMO

2, 0 < x < 1, M = Mn, Co, Ni, etc.), which exhibit high specific capacity due to additional anionic redox activity and have been extensively studied, are regarded as promising commercialized cathode materials [

40,

41,

42,

43]. However, the anionic redox reaction activated by high charging voltage can lead to excessive lattice oxygen oxidation and irreversible release, followed by the promotion of the migration and dissolution of transition metals, and finally, resulting in the decay of the phase structure [

44,

45,

46]. Meanwhile, released oxygen can undergo violent interfacial side reactions with the electrolyte, consuming active lithium ions and further hindering lithium-ion diffusion while activating low-voltage redox couples [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52]. These behaviors contribute to reduced initial Coulombic efficiency, weakened rate performance, and accelerated decay of cycling capacity and voltage [

53,

54,

55]. To address these challenges and chart future advancements in LRM, it is essential to thoroughly understand their physical and chemical properties and identify potential solutions.

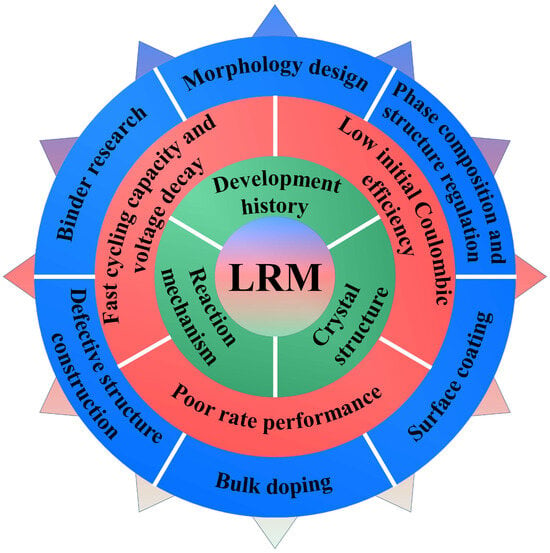

In this review, the history of development, the contradiction of crystal structure, and the diversity of reaction mechanisms of LRM are first introduced comprehensively. Then, the original causes of existing challenges of LRM are analyzed in detail, and the principle and recent progress of modification strategies developed to address these existing challenges are emphatically described. After that, the future development of LRM is prospected from the material level, modification strategy level, and full lifecycle level. This work helps to deepen the understanding of LRM and promote their large-scale commercial application.

2. Development History of LRM

The development of LRM can be traced back to the study of lithium manganese oxide by Johnston and Heikes in 1956. They synthesized the Li

xMn

1−xO system and studied its composition, structure, and magnetic properties [

56]. After that, lithium manganese oxide was used as a cathode material for lithium-ion batteries due to its advantages, such as reversible lithium-ion extraction and insertion, environmental friendliness, and low cost [

57,

58,

59]. However, spinel-structured lithium manganese oxides (such as LiMn

2O

4) do not possess a specific capacity advantage over commercial LiCoO

2 cathode materials [

57,

60,

61]. Although layered lithium manganese oxides (such as LiMnO

2 [

28,

62] and Li

2MnO

3 [

59,

63]) have potential specific capacity advantages, their electrochemical stability is poor due to factors such as Mn migration and phase transition [

64]. To enhance the electrochemical stability of layered lithium manganese oxides, researchers attempted to introduce other elements to replace part of Mn ions, forming stable layered LiMO

2 compounds. These substitution methods include single-element substitution (such as Al [

65], Cr [

66], Co [

67,

68], and Ni [

69]) and multi-element substitution (such as Co and Ni [

70]). Furthermore, the layered Li

2MnO

3 compound was integrated with the LiMO

2 compound [

70]. As a result, the prepared LRM showed enhanced electrochemical stability and ultra-high specific capacity output over a wide range of charge and discharge voltages [

71].

3. Crystal Structure of LRM

The crystal structure of LRM is challenging to identify due to the similarity and complexity of the crystal structures of LiMO

2 (space group R-3m) and Li

2MnO

3 (space group C2/m) [

72,

73,

74,

75]. As shown in

Figure 1, researchers have established single-phase solid solution and multi-phase composite models, respectively, for the existence of LiMO

2 and Li

2MnO

3 phases in the form of layered single-phase solid solution [

76,

77,

78,

79] or multi-phase composite [

61,

80]. The main dispute between these models concerns the distribution of M atoms in the transition metal layer. Some researchers believe that M atoms are uniformly mixed in the transition metal site; the chemical formula can be written as Li

1+xM

1−xO

2 (0 < x < 1). They base this on the linear relationship between the lattice constant of LRM and the proportion of LiMO

2 and Li

2MnO

3 components, which follows Vegard’s law of solid solutions [

81]. This is supported by transmission electron microscopy and electron diffraction results revealing single-phase solid solution type LRM with either C2/m [

82] or R-3m space group [

83,

84]. Additionally, some researchers believe that there are separation and local clusters of M atoms in the transition metal layer, and the chemical formula can be written as xLi

2MnO

3·(1−x)LiMO

2 (0 < x < 1), as evidenced by transmission electron microscopy and electron diffraction results that reveal the existence of multi phases and their heterointerfaces in LRM [

85,

86,

87]. Although both models are supported by experimental evidence, the controversy persists because X-ray diffraction and electron diffraction results can be affected by stacking fault [

88,

89], preventing accurate determination of fine crystal structure information [

82,

90]. Moreover, transmission electron microscopy results are usually obtained only from the local lattice region. Therefore, to determine the crystal structure of LRM, further advanced characterization methods paired with computational simulations are still needed to comprehensively highlight the advantages of various methods and verify the reliability of evidence from all perspectives [

74].

4. Reaction Mechanism of LRM

The reaction mechanism of LRM involves changes in charge and discharge curves, the origin of high specific capacity, and crystal structure evolution. The change in charge and discharge curves is mainly reflected in the difference between the charge and discharge curves at the initial and second cycles, as shown in

Figure 2a,b [

80,

91]. During the initial charging from point 1 to point 2, lithium ions are removed from the LiMO

2 phase. With the increase in the charging voltage, there is a voltage plateau in the voltage range from point 2 to point 3, owing to lithium-ion extraction and oxygen release in the Li

2MnO

3 phase. During the initial discharging process, lithium ions continue to embed into the LRM over the voltage range from point 3 to point 4. Compared to the initial cycles, although the voltage plateau in the charge curve of the second cycle is no longer present, the voltage hysteresis between the charge and discharge curves reduces.

LRM exhibits a significantly higher specific capacity compared to what is contributed by cationic redox reactions. The additional specific capacity is typically attributed to anionic redox reactions. Partial lattice oxygen can contribute to specific capacity through the reversible conversion of O

2− and O

22− states during the charging and discharging process of LRM [

92]. Regarding the source of partial lattice oxygen activity, compared with conventional Li-M oxides, lithium-rich Li-M oxides feature an oxygen atomic coordination structure consisting of two Li-O-M and one Li-O-Li configuration [

93]. In the Li-O-M configuration, O 2p orbitals form hybridized molecular orbitals with the transition metal. However, due to the large energy difference between O 2p and Li 2s orbitals in the Li-O-Li configuration, hybridized molecular orbitals between O 2p and Li 2s orbitals cannot form. The energy level of such a Li-O-Li state is intermediate between the hybridized O bonding states and the anti-bonding transition metal states. When the charging voltage is raised to the high voltage segment, O 2p orbitals in the Li-O-Li configuration preferentially release electrons, stimulating oxygen redox reactions for charge compensation [

74,

93].

The crystal structure evolution process in LRM involves the gradual loss of lithium ions from the transition metal layer of the Li

2MnO

3 phase due to repeated lithium-ion removal and insertion during cycling. This leads to an irreversible transformation of the Li

2MnO

3 phase into a LiMO

2 phase [

94]. Moreover, nickel ions migrate from the bulk lattice to the surface lattice during cycling, thus forming a nickel-deficient bulk region and a nickel-rich surface reconstruction layer [

95]. Furthermore, along with internal phase transformation and transition metal ion migration, lattice breakdown, vacancy condensation, micro-cracks, and pore accumulation will gradually occur in the bulk phase. These changes cause lattice distortion and amorphous conversion of internal grains in the bulk, gradually leading to the formation of spinel phases with different orientations [

94,

96].

5. Key Challenges of LRM

LRM exhibits high specific capacity due to the additional anionic redox activity. However, anionic redox reactions activated at high charging voltage can cause a series of problems (

Figure 3), including irreversible oxygen release, surface/interface structural phase transitions, transition metal dissolution, and interfacial side reactions. These issues will destroy the crystal structure, block the lithium-ion diffusion pathway, and hinder charge transfer, thereby reducing the initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE), deteriorating the rate performance, and exacerbating the fading of capacity and voltage, which greatly limits the large-scale commercial viability of LRM [

97,

98,

99].

A low ICE is numerically represented by an initial charging-specific capacity that is significantly higher than the initial discharging capacity. The reason is that the voltage plateau at a charging voltage exceeding 4.4 V in the LRM’s charging curve contributes significantly to the initial specific charging capacity, but this voltage plateau is irreversible during the initial discharge cycle [

100,

101]. The disappearance of the voltage plateau in the initial discharge curve means that a large number of lithium-ions removed from the LRM during the initial charging process are not embedded back into the LRM during the subsequent discharging process. Lithium-ion failure to reinsert into the LRM may result from lattice oxygen release, crystal structure phase transitions, transition metal ion migrations, and blockages or collapses of lithium-ion return paths to their original points [

102,

103,

104].

The rate performance of LRM is primarily limited by lithium-ion diffusion rates within the material and charge transfer rates at the electrode/electrolyte interface [

105,

106]. Among them, several factors contribute to limiting lithium-ion diffusion in LRM, which can be divided into three main categories. Firstly, during the charging process, lithium-ion in the transition layer of the Li

2MnO

3 phase must migrate to the lithium layer via stabilized tetrahedral sites, and the overall migration path is longer and the repulsion effect is relatively larger during the migration process compared to that of lithium-ion in the LiMO

2 phase [

107]. Meanwhile, the Li

2MnO

3 phase and its active MnO

2 components exhibit poor kinetics, and the dynamic barrier of lithium-ion diffusion at the interface between the Li

2MnO

3 component and electrolytes is higher [

105]. Secondly, the diffusion path of lithium-ion can only be along the direction parallel to the lithium layer, and the crystal face perpendicular to the lithium layer has no electrochemical activity for the transport of lithium-ion, preventing them from providing a suitable path for lithium-ion transport [

108,

109,

110]. Thirdly, due to the poor electrical conductivity of the Li

2MnO

3 phase, LRM exhibits low electrical conductivity [

105,

106,

111].

Serious voltage and capacity decay during cycling is mainly due to the release of lattice oxygen, which triggers the conversion of redox couples, defect formation, phase structure transformations, and interfacial side reactions [

52,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116]. During the initial cycle, the capacity is primarily provided by redox couples, such as Ni

2+/Ni

3+, Ni

3+/Ni

4+, and O

2−/O

−, but the release of lattice oxygen will activate lower voltage redox couples, such as Mn

3+/Mn

4+ and Co

2+/Co

3+, resulting in a continuous decrease in the average valence state of transition metal ions and then accelerate the voltage decay [

52]. Meanwhile, a decrease in the Mn element’s valence state stimulates the Jahn–Teller effect, which intensifies Mn element dissolution [

113,

114,

117]. Moreover, triggering anionic redox reactions reduces the formation energy and diffusion barriers of oxygen vacancies, leading to nanohole formation and crystal structure transformations [

115,

118]. Over time, the layered LRM structure gradually transforms into a spinel and disordered rock-salt phase [

113]. In addition, the released lattice oxygen will aggravate the interfacial side reaction and further deteriorate the cycling performance [

114].

6. Modification Strategies of LRM

Considering the significant challenges faced by LRM, current modification strategies primarily center on morphology design, phase composition and structure regulation, surface coating, bulk do**, defective structure construction, and binder research.

6.1. Morphology Design

Morphology design primarily involves controlling the initial precursor morphology by adjusting preparation methods and process parameters during the precursor’s production. This ultimately leads to obtaining the desired final morphology through subsequent high-temperature sintering [

119,

120,

121,

122,

123]. LRM exhibits a wide variety of morphologies, such as fusiform porous micro-nano structure [

119], double-layer hollow microspheres [

120], nanowires [

121], irregular particles [

122], and three-dimensional cube-maze-like structures [

123]. To prepare double-layer LRM hollow microspheres, Ma et al. [

120] employed the co-precipitation method to synthesize spherical transition metal hydroxide precursors. They then pre-calcined the precursors to form corresponding transition metal oxides, achieving a hollow structure in the spherical transition metal oxides by controlling the pre-calcination temperature. Mixing the transition metal oxide with lithium hydroxide and calcining at high temperatures resulted in the target morphology (

Figure 4a). The synthesized double-layer LRM hollow microspheres enhanced structural stability and optimized lithium-ion diffusion paths and charge transport characteristics, leading to significant rate performance improvement (

Figure 4b). Additionally, Liu et al. [

123] used the hydrothermal method to prepare a three-dimensional cube-maze-like carbonate precursor by controlling the proportion of solvent components. They combined this approach with solid phase sintering to produce a three-dimensional cube-maze-like LRM with exposed {010} active planes (

Figure 4c). The three-dimensional cube-maze-like architecture increases specific surface area and shortens lithium-ion diffusion paths, ultimately enhancing the rate capability and cycling stability of LRM (

Figure 4d).

6.2. Phase Composition and Structure Regulation

Phase composition and structure regulation primarily involve adjusting the component distribution and structural frameworks during both precursor and final LRM production [

124,

125,

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132]. Firstly, for phase component regulation, Wu et al. [

124] synthesized agglomerated-sphere LRM with a concentration gradient in the phase component using the co-precipitation method.

Figure 5a illustrates that Mn element concentration decreases linearly from the particle center to the surface, while Ni and Co element concentrations increase linearly. By combining high-capacity particle center and cycle-stable surface phases, voltage fading is effectively suppressed, and cycling stability is improved (

Figure 5b, c). Secondly, for phase structure regulation, transition metal ions can migrate into lithium sites within the lithium layer relatively easily through tetrahedral sites between the transition metal layer and the lithium layer in conventional O3-type LRMs. This irreversible migration leads to structural rearrangement and voltage attenuation [

125,

126,

127,

128]. Eum et al. [

128] used the ion exchange method to prepare O2-type LRM to inhibit this phenomenon. In the O2-type phase structure, face-shared transition metal ions generate strong electrostatic repulsion, preventing their transfer to lithium sites. Additionally, these face-shared sites promote reversible transition metal ion transfer back to the original sites in the transition metal layer during discharge. Finally, co-regulation of phase composition and structure can also be employed. For example, constructing the spinel/layered heterostructure [

129,

130,

131,

132] with good structural compatibility creates three-dimensional lithium-ion diffusion channels, enhances lattice oxygen stability, and restrains phase transitions and interfacial side reactions. This approach improves the rate and cyclic performance of LRM.

6.3. Surface Coating

Surface coating primarily serves to protect LRM from direct electrolyte erosion, stabilize surface lattice oxygen, inhibit phase transitions, and reduce interfacial side reactions [

133,

134,

135,

136,

137,

138,

139,

140,

141,

142,

143,

144,

145,

146]. Surface coating materials can be broadly divided into three categories. The first category is active materials containing lithium, such as Li

2MnO

3 [

133], Li

4V

2Mn(PO

4)

4 [

134], and LiFePO

4 [

135]. Kim et al. [

133] used dip-dry combined with high-temperature calcination to coat Li

2MnO

3 with the same crystal framework as the bulk phase on the surface of LRM, achieving a seamless interface connection that effectively reduces transition metal ion mixing and inhibits phase transitions. The second category consists of non-active materials without lithium, including oxides [

136,

137], phosphates [

138,

139], and fluorides [

140,

141]. Zhang et al. [

136] applied atomic layer deposition technology to construct Al

2O

3 and TiO

2 coatings on the surface of LRM. Since the TiO

2 coating appeared as particles on the surface of LRM, while the Al

2O

3 coating showed good uniformity and consistency, materials with the Al

2O

3 coating layer exhibited better cycling stability. The third category comprises functional materials, such as fast ionic conductors [

142,

143,

144], piezoelectric materials [

145], and dielectric materials [

136]. Xu et al. [

144] used potassium Prussian blue with good ion conduction properties as the coating material for LRM (

Figure 6a). The three-dimensional open frame structure of the potassium Prussian blue coating layer provides sufficient interstitial sites and transmission channels for lithium-ion transport, protecting LRM from electrolyte corrosion and inhibiting interfacial side reactions. As a result, the coated sample displays remarkably enhanced rate capability and cycling stability (

Figure 6b,c).

6.4. Bulk Do**

Bulk do** involves introducing dopants during the precursor’s production to enhance lithium-ion transport by expanding diffusion channels, suppressing transition metal ion migration, and stabilizing lattice oxygen through a pinning effect [

48,

147,

148,

149,

150,

151,

152,

153,

154,

155,

156,

157,

158,

159,

160,

161,

162,

163,

164,

165,

166]. Do** can be carried out in single-ion or multi-ion forms, with single-ion do** involving either a single cation or anion. Commonly used single cations include Na

+ [

147,

148,

149], K

+ [

150], Mg

2+ [

151], Al

3+ [

48], Sb

3+ [

152], Nb

5+ [

153] and W

6+ [

154,

155]. He et al. [

148] introduced Na

+ ions into the co-precipitation process for carbonate precursor synthesis, achieving a uniform distribution of Na

+ in the LRM. The uniform distributed Na

+ effectively inhibited detrimental solid–liquid interface corrosion and transition metal ion migration, enhancing structural and cyclic stability. Single anions commonly employed are F

− [

156,

157], S

2− [

158], and polyanion [

159]. Li et al. [

159] directly incorporated boracic polyanion to regulate the electronic structure during LRM preparation via the sol-gel method. The lowered M–O bond covalence and decreased top of the O 2p band mitigated changes in the electronic structure of the O 2p band during charging and discharging, improving thermal and cycling stability (

Figure 7a–c). In addition, various multi-ions can be used, such as (Na

+ and Si

4+) [

160], (Al

3+ and Ti

4+) [

161], (Ni

2+ and SO

42−) [

162], (Fe

3+ and Cl

−) [

163], (Nb

5+ and F

−) [

164] and (Na

+ and F

−) [

165,

166]. Among these, Zheng et al. [

166] introduced both Na

+ and F

− ions in the solvothermal preparation process of the precursor (

Figure 7d). The additional formation of Na–O and TM–F bonds regulated the local atomic structure and reduced the energy of the TM 3d-O 2p and non-bonding O 2p bands. This led to a reduction in lithium-ion diffusion activation energy and an increase in oxygen vacancy formation energy, simultaneously improving lattice oxygen stability, rate performance, and cycling stability (

Figure 7e,f).

6.5. Defective Structure Construction

The construction of the defective structure is achieved by regulating reaction conditions during the addition of a lithium source and subsequent calcination process or surface modification for the final LRM product. The benefits include reducing lithium-ion diffusion energy barriers and improving surface lattice oxygen stability [

167,

168,

169,

170,

171,

172,

173]. Common defects include cationic vacancies [

167,

168], anionic vacancies [

169,

170,

171], and other types of defects [

170,

172,

173]. Cationic vacancies, such as lithium vacancies, were constructed by Liu et al. [

167] by controlling the amount of the added lithium source in the calcination process (

Figure 8a). This effectively lowered the diffusion energy barrier of lithium ions and improved the utilization rate. Meanwhile, the in situ formation of lithium vacancies induced the development of surface spinel coating and Ni-do** in the lithium layer. The combined strategies resulted in enhanced initial Coulombic efficiency, rate performance, and cycling stability of LRM (

Figure 8b–e). For anionic vacancies, such as oxygen vacancy, Qiu et al. [

169] used the decomposition of ammonium bicarbonate to perform a gas–solid interface reaction with LRM, creating oxygen vacancies. The presence of oxygen vacancies increased lithium-ion mobility, limited surface gas emissions, and reduced interface impedance, thereby enhancing rate performance. Regarding other types of defects, such as stacking faults, Liu et al. [

172] prepared LRM with varying degrees of stacking faults by controlling the type of molten salt and reaction temperature in the molten-salt method. They found that samples with more stacking faults showed higher reversible capacity.

6.6. Binder Research

The primary purpose of binder research is to inhibit transition metal ion transfer and improve adhesion to LRM. In addition to commonly used polyvinylidene fluoride, other binders include polyacrylic acid and polyacrylonitrile [

174,

175]. For example, Yang et al. [

174] employed polyacrylic acid as the binder (

Figure 9a). This effectively isolated and mitigated electrolyte erosion on LRM. The hydrogen ions in polyacrylic acid can exchange with the lithium ions on the LRM surface, forming a proton-doped surface layer that hinders transition metal ion transfer. This process reduces voltage decay and enhances cycling stability (

Figure 9b, c). Additionally, Xu et al. [

175] used polyacrylonitrile as a binder (

Figure 9d). The carbon–nitrogen triple-bond in polyacrylonitrile can form coordination bonds with unstable transition metal ions on the LRM surface. These bonds increase the migration energy barrier for irreversible transition metal ions transfer. Meanwhile, the coordination bond enhances the adhesion between polyacrylonitrile and LRM, reducing electrolyte erosion and improving adhesion to the aluminum foil current collector. This results in enhanced voltage and cycling stability (

Figure 9e, f).

7. Summary and Prospects

In this review, the development history, synthesis methods, crystal structure, and reaction mechanism of LRM are introduced, and the current key challenges are analyzed. Then, the recent progress of modification strategies to overcome these challenges is described in detail. While these strategies have mitigated problems such as low initial Coulombic efficiency, poor rate performance, fast cycling capacity and voltage fading to a certain extent, there remain numerous challenges at different levels that need to be considered and solved in future research work for the commercial viability of LRM.

The first challenge is at the material level. Voltage decay and hysteresis are still critical electrochemical performance issues that need to be solved. To solve these problems, it is urgent to deepen the comprehension of the crystal structure and reaction mechanism of LRM. In the future, advanced characterization techniques and computational simulation methods could be used to identify the unresolved crystal structure and clarify the unresolved reaction mechanism at the atomic and energy levels. This would establish a clear structure–activity relationship and further improve the comprehensive electrochemical performance of LRM. Additionally, LRM exhibits physicochemical property issues, such as poor electrical conductivity, slow ion diffusion, and low tap density. In the future, the electrical conductivity, ion diffusion rate, and structural stability of LRM could be improved by constructing a strong network structure of full-surface conductive coating connected with primary particles. Meanwhile, the tap density can be enhanced by filling the internal pores of secondary particles or preparing quasi-monocrystalline LRM.

At the second level, modification strategies have been proposed to address current issues in LRM. However, a single strategy typically addresses part of the problems, and their improvement effects need further enhancement. Therefore, there is an urgent need to refine and integrate existing modification strategies to improve the comprehensive performance of LRM. To enhance the modification strategy, firstly, it is necessary to systematically summarize the process design principles by combining experimental results and theoretical calculation methods. This includes understanding the principle for selecting dopant elements and coating material, as well as lattice matching between coating material and LRM. The second is to improve the accuracy of the modification strategy. This can be achieved through advanced characterization technologies that enable observation and optimization of process conditions, ensuring fixed-point and quantitative do**, coating, and surface interface structure control. Regarding the integration of modification strategies, the modification process can be deeply integrated into the necessary preparation process of LRM, and the integration and comprehensive application of multiple modification strategies can be realized without adding additional process steps and costs. For example, during precursor preparation, morphology and phase composition ratios could be regulated, and dopants could be added. Alternatively, dopants can be introduced during the mixed lithium source stage, followed by simultaneous construction of defects, do**, coating layer, and heterointerface structure during the surface/interface structure optimization process for LRM.

The final level concerns the full lifecycle of LRM, which includes several critical stages that require attention: mass production, packaging and storage, material matching, battery manufacturing, non-destructive testing, failure analysis, cascade utilization, repair activation and recycling. Each key node presents its own set of challenges. Although LRM application in automotive power batteries still requires extensive research, it is possible to select scenarios that prioritize high specific capacity but have lower performance requirements for other aspects. Existing LRM can be applied to manufacturing batteries that are tested and optimized to overcome the critical issues at each node in the full lifecycle of LRM, facilitating their application in more suitable fields. To cater to a broader range of application scenarios, it is essential to continue develo** new types of LRM, such as cobalt-free, manganese-rich, high-voltage, solid-state, and wide-temperature-range variants. This ongoing development will help ensure the successful commercialization of LRM.

Share and Cite

MDPI and ACS Style

Guo, W.; Weng, Z.; Zhou, C.; Han, M.; Shi, N.; **e, Q.; Peng, D.-L.

Li-Rich Mn-Based Cathode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries: Progress and Perspective. Inorganics 2024, 12, 8.

https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics12010008

AMA Style

Guo W, Weng Z, Zhou C, Han M, Shi N, **e Q, Peng D-L.

Li-Rich Mn-Based Cathode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries: Progress and Perspective. Inorganics. 2024; 12(1):8.

https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics12010008

Chicago/Turabian Style

Guo, Weibin, Zhangzhao Weng, Chongyang Zhou, Min Han, Naien Shi, Qingshui **e, and Dong-Liang Peng.

2024. "Li-Rich Mn-Based Cathode Materials for Li-Ion Batteries: Progress and Perspective" Inorganics 12, no. 1: 8.

https://doi.org/10.3390/inorganics12010008

Note that from the first issue of 2016, this journal uses article numbers instead of page numbers. See further details

here.

Article Metrics

Article Access Statistics

For more information on the journal statistics, click

here.

Multiple requests from the same IP address are counted as one view.